The Art of No Debate

In this episode of Enlightenment Today I will explore the Eastern resistance to debating, especially in countries such as Japan. Avoiding debate is another hallmark of Eastern thought that a lot of Westerners find hard to comprehend. In the West we are almost encouraged to debate so we can come to a conclusion on a matter. This way of thinking is incorrectly believed to be universal. Westerners often think that the way they think is the same for everyone else. This is a clumsy way of viewing the world. Both East and West cognitively evolved differently which influenced their social structures, philosophies, religions, language, and basic world view. In the West debate was a natural byproduct of analytical thinking and individualism. While in the East, avoiding debate was a natural byproduct of holistic thinking and collectivism.

Spiritual Materialism

In this episode Enlightenment Today I will explore spiritual materialism. I’m going to explain why people feel the need to show their spirituality on the outside. This means that I’m going to put under the microscope all of our dreadlocks, tattoos, piercings, and other accessories.

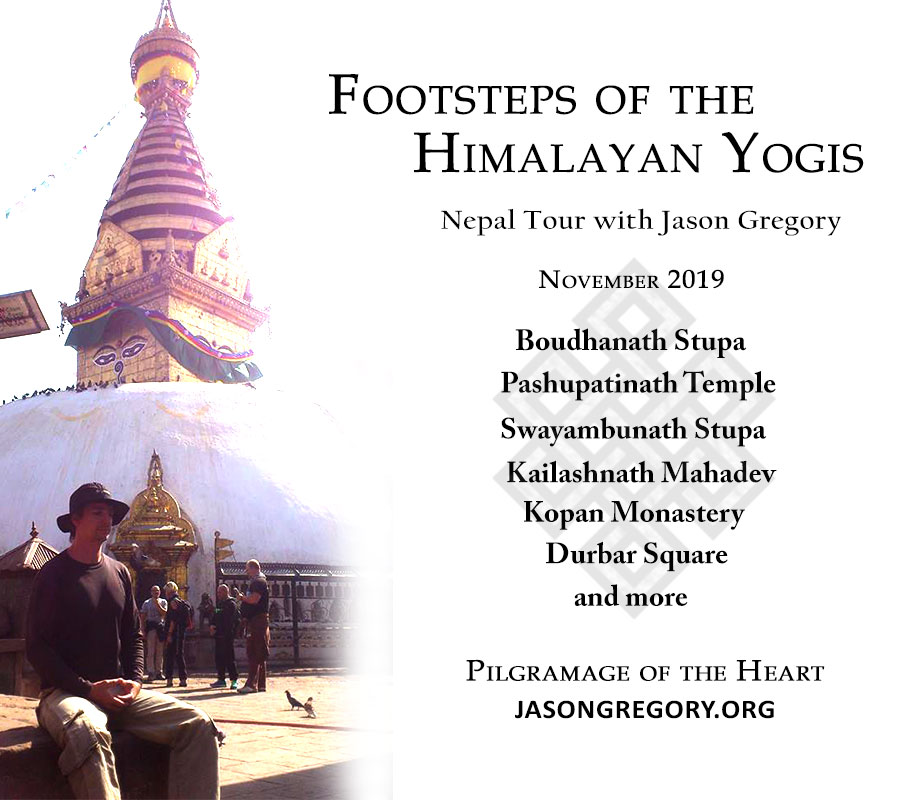

Footsteps of the Himalayan Yogis Nepal Tour 2019 with Jason Gregory

FOOTSTEPS OF THE HIMALAYAN YOGIS NEPAL TOUR with Jason Gregory 16-25 NOVEMBER 2019 The Footsteps of the Himalayan Yogis Nepal Tour is one of the most unique travel experiences in the world. You can travel with author, philosopher, and spiritual teacher Jason Gregory on a mystical tour of Nepal to explore and trace the footsteps of the Himalayan yogis. Get unique insights into Jason’s knowledge of the East and the memory of the masters and scared places you will visit. Jason wishes to take people to the most sacred places in the sacred Kathmandu valley to show that the ancient Hindu and Buddhist cultures are thriving. But this can only be experienced by those willing to join him on this pilgrimage of the heart. 1. About the tour of Nepal: Our 10-day itinerary includes visits to the most breathtakingly beautiful and mystical places of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal. We will travel through Nepal to visit the most important sacred places of Nepalese history. Most people never get the chance to experience face to face the archaic origins and sacred sites of Hindu and Buddhist culture. But on this journey you will get a once in a lifetime opportunity to actually feel the ancient living culture that is still thriving in the sacred places you will visit. You will also get the chance to meet real life mystics and mingle with the beautiful people of Nepal. What is more, during the tour you will take part in private discourses given by Jason Gregory. He will show you the significance of how the great Eastern spiritual traditions can help you live more harmoniously in the modern world. You will begin to understand the deep wisdom the mystics of the East expounded for you to find true happiness and fulfillment in this life. And this is the reason for joining Jason Gregory on his tour of Nepal to follow the Footsteps of the Himalayan Yogis. This is a once in a life-time experience! Jason Gregory about the Nepal tour: “I have spent several years in Nepal and the experience has changed the entire course of my life. I continue to go back and visit every year. One of my favorite places in the world is the sacred Kathmandu Valley. The Hindu and Buddhist pilgrimage sites in the Kathmandu Valley are some of the most powerful and peaceful you will visit in the world. There is something magical about being in the Himalayas that the ancient Hindus and Buddhists understood. The mountains have a mystical presence that have attracted mystics for thousands of years. This is why the Kathmandu Valley is significant, as it is in the heart of the Himalayas. And luckily for all those on tour, we will be in this heart of the Himalayas that the mystics believed to be sacred. I have always told people that Nepal is hard to explain, the attraction people have to it, and its transformative ability on an individual. It is a place full of color, where the culture is vibrant and the people humble. Kathmandu Valley is a unique blend of past and present. My life in Nepal has not just been transformed by their ancient spiritual traditions, but also from the humble nature of the people and beautiful culture. This spiritual essence you experience in Nepal comes from thousands of years of people focused on the inner realm of spirituality that has led to many great sages and stories of enlightenment in the Himalayas. On this tour, I want to allow people to experience this living spirit that we feel when we are in the culture of Nepal by following the footsteps of the Himalayan Yogis. My experience of living in Nepal for several years allows me to take you on an insider’s journey of Nepal on this tour, where you will come face to face with the Himalayan soul. Plus you’ll also have a lot of fun, fun like you’ve never had before.” 2. ITINERARY Day 1 – Arrival to Kathmandu (16 November 2019) Arrival at Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu. A representative of the tour team will welcome guests at the Tribhuvan International Airport and transport them to the hotel. After the check-in process at the hotel, guests will have time to rest and recuperate while all guests arrive at the hotel. Day 2 – Boudhanath & Pashupatinath Temple (17 November 2019) On day 2 we will explore two of the most sacred sites for Buddhists and Hindus in the Kathmandu Valley. In the morning we will visit Boudhanath, one of the largest spherical stupa’s in the world because of its massive mandala. The Boudhanath Stupa is a sacred place of pilgrimage for Buddhists. We will circumambulate the stupa many times in meditation. Later we will enjoy all the wonderful shops and culture that are thriving in Boudhanath. In the late afternoon we will visit the famous Pashupatinath Temple located along the Bagmati River. This is a very sacred temple for Hindus and considered the most sacred place in Nepal. The temple serves as the seat of Nepal’s national deity, Pashupati, who is an incarnation of the Hindu god Shiva. We will explore the temple complex, visiting the ritual cremation ghats and also the many sadhus along the banks of the Bagmati River. In the early evening we will attend the Pashupatinath Bagmati Aarti, a sacred Hindu ritual performed along the banks of the Bagmati River. Day 3 – Bhaktapur Durbar Square (18 November 2019) On day 3 we will travel to the ancient city of Bhaktapur and visit the famous Bhaktapur Durbar Square. Bhaktapur is the largest of three Newar kingdoms, the other two kingdoms are Kathmandu and Patan. All three are the home to a Durbar Square (royal palace), but Bhaktapur Durbar Square is the most impressive. It actually consists of four distinct squares (Durbar Square, Taumadhi Square, Dattatreya Square and Pottery Square). It has Hindu and Buddhist iconography scattered all throughout the complex. We will explore this ancient complex all throughout the day. Day 4 – Kopan Monastery & Pullahari

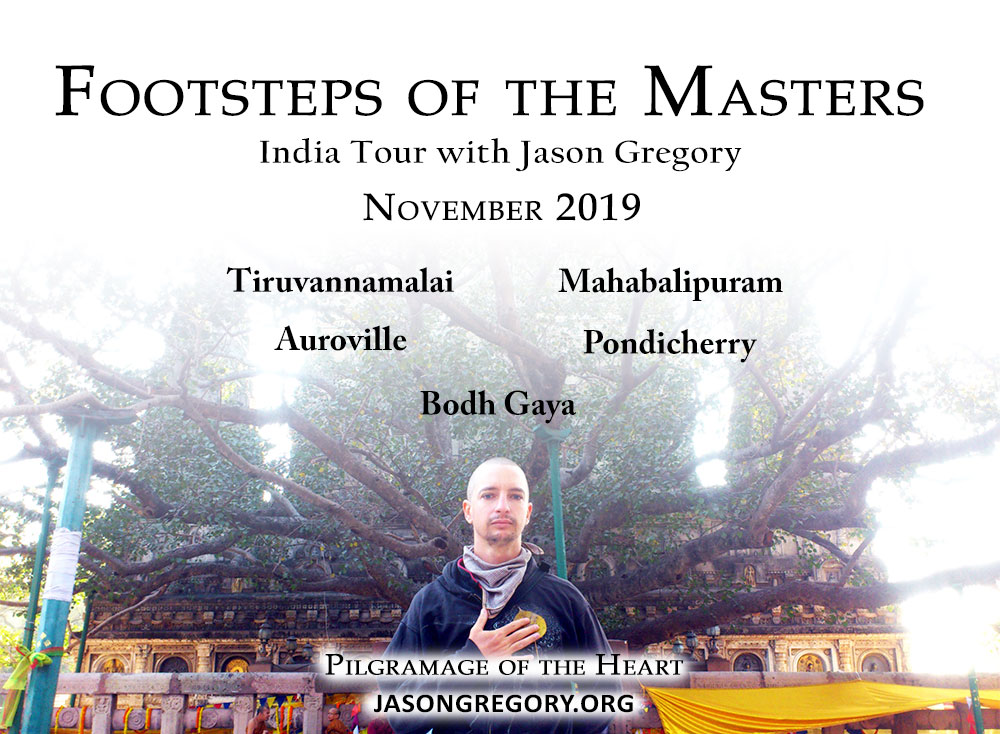

Footsteps of the Masters India Tour 2019 with Jason Gregory

FOOTSTEPS OF THE MASTERS INDIA TOUR with Jason Gregory 1-13 NOVEMBER 2019 The Footsteps of the Masters India Tour is one of the most unique travel experiences in the world. You can travel with author, philosopher, and spiritual teacher Jason Gregory on a mystical tour of India to explore and trace the footsteps of the masters. Get unique insights into Jason’s knowledge of the East and the memory of the masters and scared places you will visit. Jason wishes to take people to the most sacred places of India to show that the ancient Hindu and Buddhist cultures are thriving but can only be experienced by those willing to join him on this pilgrimage of the heart. 1. About our tour to India: Our 13-day itinerary includes visits to the most breathtakingly beautiful and mystical places in India. We will travel through India to visit the most important sacred places of Indian history. Most people never get the chance to experience face to face the archaic origins and sacred sites of Hindu and Buddhist culture. But on this journey you will get a once in a lifetime opportunity to actually feel the ancient living culture that is still thriving in the sacred places you will visit. You will also get the chance to meet real life mystics and mingle with the beautiful people of India. What is more, during the tour you will take part in private discourses given by Jason Gregory. He will show you the significance of how the great Eastern spiritual traditions can help you live more harmoniously in the modern world. You will begin to understand the deep wisdom the mystics of the East expounded for you to find true happiness and fulfillment in this life. And this is the reason for joining Jason Gregory on his tour of India to follow the Footsteps of the Masters. This is a once in a life-time experience! Jason Gregory about the India tour: “I have spent several years in India and the experience has changed the entire course of my life. I continue to go back and visit every year, especially the Tamil Nadu and Bihar states as they are home the two places in the world I believe everybody should visit, Tiruvannamalai and Bodh Gaya, and we will be visiting both places on this tour. I have always told people that India is hard to explain, the attraction people have to it, and its transformative ability on an individual. It is a place that most people dislike from a distance because of real life hardships that people witness in India. But I have always implored people to persevere with her grace because if you can get past all the things that push you out of your comfort zone, there is an underlying essence of spirit that is only found in India, but you need to give her time and be open to new experiences. Many believe this comes from thousands of years of people focused on the inner realm of spirituality that has led to many great sages and stories of enlightenment in India. On this tour I want to allow people to experience this living spirit that we feel when we are in the culture of India by following the footsteps of the masters. My experience of living in India for several years allows me to take you on an insider’s journey of India on this tour where you will come face to face with her archaic soul. Plus you’ll also have a lot of fun, fun like you’ve never had before” 2. ITINERARY Day 1 – Arrival to Chennai (1 November 2019) Arrival at Chennai International Airport. A representative of the tour team will welcome guests at the Chennai Airport and transport them to the hotel. After the check-in process at the hotel, guests will have time to rest and briefly explore Chennai. Overnight stay at the hotel in Chennai. Day 2 – Tiruvannamalai (2 November 2019) Travelling to Tiruvannamalai. Tiruvannmalai is considered one of the most sacred places on Earth. It has the ability to transform one’s life. It is known as the City of Enlightenment for that very reason. It has been the home of sages, sadhus, and yogis for thousands of years. Tiruvannamalai is home to the holy mountain Arunachala, which is thought to be an incarnation of Shiva. Arunachala is what drew the 20th century sage Ramana Maharshi to this little Indian town, where he remained silent for 7 years up on the holy mountain in meditation. During his life on the slopes and at the foot of Arunachala disciples were attracted to his immense presence and an ashram was built around him, the famous Sri Ramana Asramam. It was here that Paul Brunton had his famous encounter with the Maharshi and consequently led to his international bestseller In Search of Secret India. This Hindu culture has never left this place, where you find sadhus descend on Tiruvannamalai every day renouncing the world to be at the foot of Arunachala and to also spend time in meditation at the Arunachaleswarar Temple (Temple of Shiva). During day 2 we will visit Arunachaleswarar Temple (Temple of Shiva) and explore its magnificent architecture and mythology. We will tour the city of Tiruvannamalai to get acquainted with the City of Enlightenment. Day 3 – Tiruvannamalai (3 November 2019) Early in the morning we will go to Sri Ramana Ashram to observe Puja (Hindu ritual worship) and also meditate in the silence of this sacred space. We will then walk up to Skanda Ashram and Virupaksha Cave where Sri Ramana Maharshi spent many years in silence. We will practice meditation in both places. Later in the day we will visit the famous Girivalam Path to visit temples and be in the presence of sadhus. Day 4 – Tiruvannamalai (4 November 2019) We will rise early again on day 4 to walk up Arunachala and visit Skanda Ashram one last time to meditate before we embark on our day. During our last day in Tiruvannamalai we will visit the Sri Ramana

Ramana Maharshi

In this episode of Enlightenment Today I will explore the life and teachings of the great 20th century sage Ramana Maharshi. His life was dedicated to the ancient spiritual tradition of Advaita Vedanta (nondualism) after his enlightenment at the young age of sixteen. Ramana Maharshi belongs in the honorable company of the Buddha, Lao-tzu, Chuang-tzu, Shankara, Patanjali, Bodhidharma, and Mahavira. His timeless teachings are imperative to understand in our busy and chaotic modern world. Recommended Reading Be as You Are http://amzn.to/2z1YML6 Who am I?: The Teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi https://amzn.to/2oIbR8w The Collected Works of Ramana Maharshi https://amzn.to/2Q6nxPd The Spiritual Teaching of Ramana Maharshi https://amzn.to/2oFQzIH NOTE: This site directs people to Amazon and is an Amazon Associate member. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. The pages on this website may contain affiliate links, which means I may receive a commission if you click a link and purchase something that I have recommended.

STOP HAVING BABIES AND SAVE THE WORLD

In this episode of Enlightenment Today I explore what overpopulation is doing to the world and why our conscious choice to refrain from having children might be the most noble act of our time. The reason I wanted to address such a contentious topic is because recently we broke the record for Earth Overshoot Day. The new record stands at August 1 for 2018 and it’s not a record we should be proud of. If people aren’t going to stop their thirst for material objects then not having children is the only responsible choice. Recommended Reading https://www.overshootday.org/

You Are Worthy

In this episode of Enlightenment Today I explore why we feel the need to be worthy and why it is wrong to feel worthless. Trying to feel worthy is common among all cultures and societies. We are all trying to prove our worth to others. We want to be accepted by others. We’ll do anything to feel as though we are needed by the world. We’ll continually chase our tail to try and be successful in the eyes of others. We’re essentially putting on an act for the world to try and establish our worth. But why do we feel the need to be someone else to please the world? Why are you not fine just the way you naturally are? The bigger question, is it normal to feel unworthy? So, basically what I’m going to address is why we feel the need to be worthy and is that attitude is even sane.

Learn to Say NO and Get to Work

In this episode Enlightenment Today I explore how to be more effective and productive in life when it comes to creating work that matters. Learn to say NO and get to work. Learning to say no and just getting to work are both two simple principles for creating meaningful content. Recommended Reading Learn to Say NO and Get to Work blog post Learn to Say NO and Get to Work

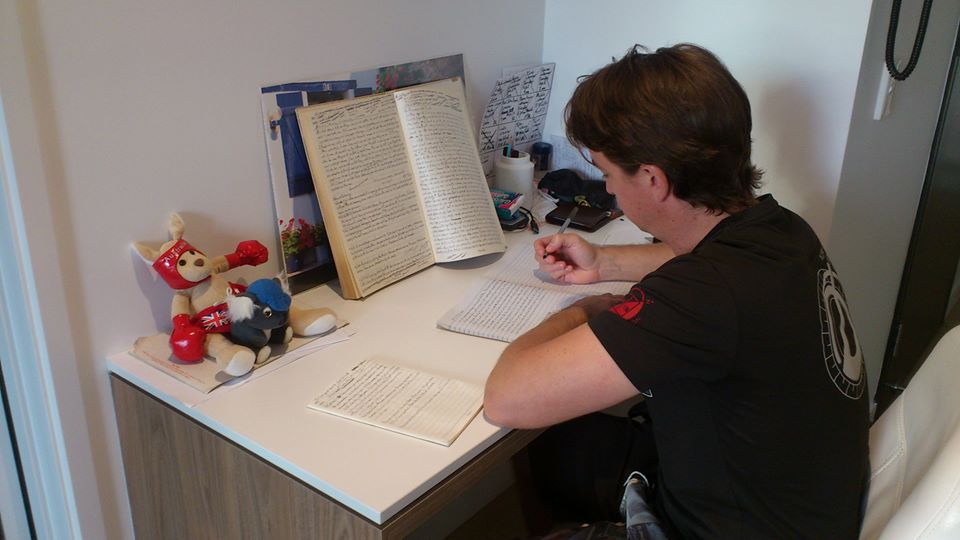

Learn to Say NO and Get to Work

Learn to Say NO and Get to Work I received an email from a budding writer. She asked, “How can I get so much done in so little time?” My answer was simple: Learn to say NO and get to work. Both are the two simple principles for creating meaningful content. Procrastination kills all artistic endeavors. The only way to slay that dragon is to get to work and guard your time because its the most precious resource we have. I’m anxious when I procrastinate, so I just get to work and see what comes to me naturally. I try not to overthink about what I want to create nor do I have illusions of grandeur. I just have a trust in the process of writing itself. I’ve learned that if you want to write, just sit down and shut up. Let the pen do the talking. Stop thinking about what you are going to do and just do it. Embrace the grind. Its better than doing nothing and telling people about what you are going to do. I’ve had many friends tell me their intentions and then they don’t back it up with actions. Nothing annoys me more than that, especially when they complain that their creative life is going nowhere. Your intention and action have to unite. This is why I don’t tell anyone what I’m writing about until I have finished. I’m currently writing my seventh book with my sixth book is in the bag. You’ll find out about both of these books when they are ready to be published. But all my work and my future projects (which I can’t tell you about yet because there is no actions to back them up) are built on learning to say NO. You can’t fulfill your creative juices if you are constantly meeting friends and family, playing with your phone, watching TV, surfing the Internet, or saying yes to every opportunity that goes your way. You need to say NO! Make it loud and clear so everyone gets the message. As a content creator, or an artist in general, large chunks of undistracted time is what you need. If you don’t cultivate this sort of creative isolation then you’ll create nothing meaningful. Think of all the great artists you have been inspired by, this is how they did it. It sounds nice to think that artists sit around coffee shops waxing lyrical about deep topics, but we don’t live in a fantasy world. It doesn’t mean an artist doesn’t love their friends and family, it just means they know what it takes to create meaningful art. Saying NO will give you the time to express your deepest nature, but you can’t sit around dreaming about it, you gotta get to work. We can all inspire the world with our own art by following these two simple principles. Do you have what it takes? Don’t be afraid to share your art and heart with the world. SHARE

An Accomplished Taoist

In this episode of Enlightenment Today you will learn what it means to be an accomplished Taoist. We often hear people say they follow the Tao, the Way. But what does it mean and are they truly a Taoist or are they just intuiting their experience according to their own biases and confusing it with flow? When we think of Taoism we have to revert back to the two great sages of Taoist philosophy: Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu. The core of Taoism is a way of life focused on having healthy and sane people who are then capable of understanding and aligning with the spiritual core and order of the universe, the Tao. This in turn creates a healthy and sane world. By becoming an accomplished Taoist you will be immune to the inevitable perils you encounter in life. Recommended Reading Readings in Classical Chinese Philosophy http://amzn.to/2EgVpTN Tao Te Ching (Gia-Fu Feng & Jane English translation) http://amzn.to/2z6w7V3 Tao Te Ching (Philip J. Ivanhoe translation) http://amzn.to/2iCs0tU Tao Te Ching (Stephen Mitchell translation) http://amzn.to/2hPV6IX The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu http://amzn.to/2hFc1Kt The Way of Chuang Tzu http://amzn.to/2z3VyGJ I Ching http://amzn.to/2zWMSW7 Trying Not to Try http://amzn.to/2z6l0eU Tao: The Watercourse Way http://amzn.to/2zZGn2N Genuine Pretending http://amzn.to/2iDhF04 Awakening to the Tao https://amzn.to/2KdsSBc